Lesson 1 Part B: The Disability Rights Movement

The Disability Rights Movement

In this lesson, you will learn about key events in the disability rights movement, including the role of Coloradans in this movement.

Connecting Past and Present

The Americans with Disabilities Act, or the ADA, passed in 1990 and guaranteed the civil rights of people with disabilities. The ADA remains the most comprehensive piece of disability civil rights legislation in the United States. In this section, you will learn about some events leading up to the ADA. These events constitute milestones in the contemporary disability rights movement.

The movement owes much of its success to cross-disability coalitions. The term cross-disability refers to people with different types of disabilities who are united by the shared experience of social stigma. A person with Cerebral Palsy may not have a lot in common with a person who uses a wheelchair, but they likely both understand the frustrations of inaccessible buildings and social stereotypes. The Colorado Cross-Disability Coalition is the original cross-disability coalition in Colorado, designed to help people with disabilities and their families advocate for equal rights and access. You can learn more about their mission and services at the following link: Colorado Cross-Disability Coalition/

As you read through this lesson, reflect about what you've learned about disability from your K-12 education. Is this information missing? If so, does that strike you as unusual and/or problematic? We hope that when you finish this course, you'll understand why this rich history deserves a place alongside other lessons about civil rights movements in our county.

Independent Living Movement in Berkley (1962)

Arguably, the independent living movement propelled the contemporary disability rights movement forward and started a chain of events that eventually led to the passing of the ADA. The independent living movement can be seen as an anti-institutionalization movement. The movement is a rebuke of a dark U.S. history of removing people with disabilities from mainstream society and placing them in nursing homes, specialized schools, mental institutions, and prisons. The independent living movement aims to give people with disabilities options for living in a home and in a community with self-control and self-determination as well as medical care and other resources.

Arguably, the independent living movement propelled the contemporary disability rights movement forward and started a chain of events that eventually led to the passing of the ADA. The independent living movement can be seen as an anti-institutionalization movement. The movement is a rebuke of a dark U.S. history of removing people with disabilities from mainstream society and placing them in nursing homes, specialized schools, mental institutions, and prisons. The independent living movement aims to give people with disabilities options for living in a home and in a community with self-control and self-determination as well as medical care and other resources.

The movement began in 1962 when UC Berkeley accepted Ed Roberts, a paralyzed man, but failed to provide accommodations for Roberts to attend the university. Roberts pressured UC Berkeley to provide accommodations and allow him (and other disabled students) to live independently on campus. Roberts' advocacy paid off, resulting in changed university policies and the first student-led Physically Disabled Students Program. The student group then gave rise to the first Independent Living Center in the United States.

[Image shows Ed Roberts, a white man with a goatee, strapped in a wheelchair, protesting outside. A man behind him holds a sign that says "civil rights for disabled."]

504 Sit-In in San Francisco (1977)

A major national legislative victory occurred when Congress passed the Rehabilitation Act in 1973. In addition providing federal oversight for employment, transportation, and education services, there was a small section of the document--Section 504--that stated “No otherwise qualified handicapped individual in the United States shall solely on the basis of his handicap, be excluded from the participation, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.”

These 41 words provided the first piece of anti-discrimination legislation for Americans with disabilities.

The Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (or HEW) was supposed to provide the regulations that fulfilled 504, but they sat on it for four years without enforcing items that included things like ramps, braille, curb cuts, worker rights, and education programs.

In 1977, a frustrated cross-disability coalition led a nonviolent protest from inside of the HEW building in San Francisco. The group of approximately 150 disability activists, supported on the outside by other civil rights groups like the Black Panthers, occupied the federal building for nearly a month. The goal of these "504 sit-in" protestors was to put pressure on President Jimmy Carter's administration to sign, fund, and enforce Section 504. After much media coverage and meetings with federal officials, the protestors won, and 504 was signed.

[Image shows musicians in cowboy hats entertain a large group of 504 protestors holding signs outside of HEW building in San Francisco. The back of a person in a wheelchair and a sign that reads "Rights for the disabled. Sign 504 unchanged" frames the scene.]

Denver's "Gang of 19" (1978)

The 504 sit-in spurred progress, but many institutions found ways to drag their heels. Transportation companies often cited the high costs of accommodating people with disabilities as a reason to delay substantial changes to their services. The expensive and inconvenient options for transportation left available to people with disabilities spurred members of the country's second Independent Living Center (in Denver, Colorado) to protest against inaccessible public transportation.

The 504 sit-in spurred progress, but many institutions found ways to drag their heels. Transportation companies often cited the high costs of accommodating people with disabilities as a reason to delay substantial changes to their services. The expensive and inconvenient options for transportation left available to people with disabilities spurred members of the country's second Independent Living Center (in Denver, Colorado) to protest against inaccessible public transportation.

Led by Wade Blank, former Presbyterian pastor and nondisabled civil rights organizer, a group of people with disabilities blocked Denver's Regional Transportation District(RTD) buses with their bodies and wheelchairs until "traffic in the heart of downtown Denver came to a standstill" (Mccormick-Cavanagh, 2018). Chanting "We will ride!" and refusing to move until their demands were met, RTD eventually agreed to change all of its 200+ buses to accommodate people with disabilities. The Denver protests ignited a slew of disability protests across the country and put pressure on transportation companies to make these long overdue changes.

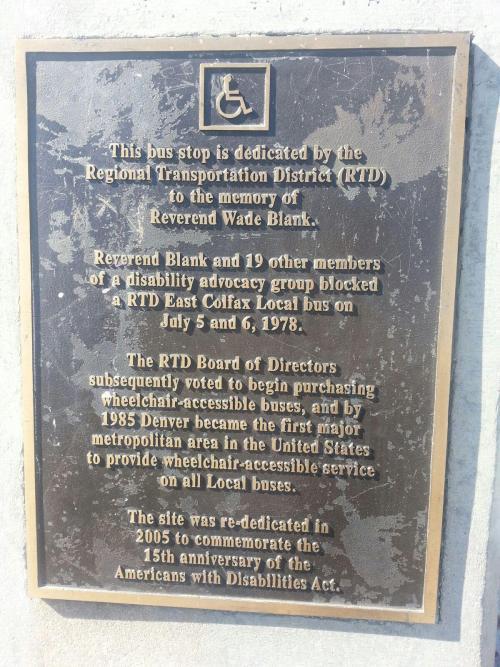

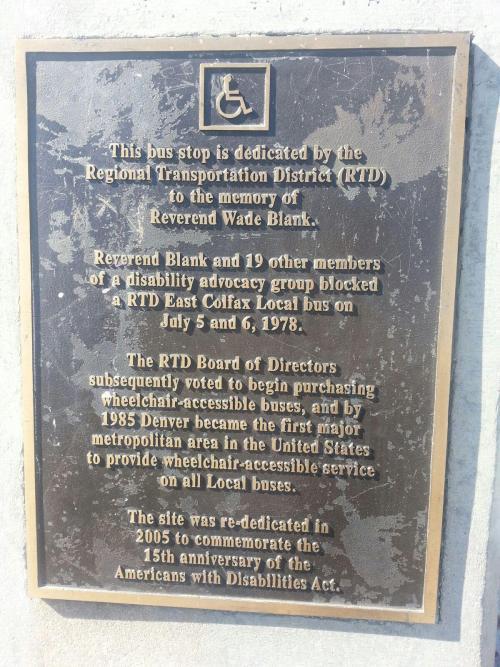

The protestors called themselves the Gang of 19 and they formed the activist organization ADAPT, which currently works from Denver's Atlantis Community, Inc. Independent Living Center. ADAPT continues to protest against anti-disability legislation, companies, and events. A plaque commemorating the group's success is located at the bus stop at Colfax and Broadway (pictured to the left). Although the organization's tactics remain controversial -- even within the disability community -- ADAPT has effectively mobilized cross-disability action, improved the self-esteem and sense of community among some stigmatized persons, and challenged rigid societal notions of people with disabilities.

[Image shows brown plaque with the message "This bus stop is dedicated by the Regional Transportation District (RTD) to the memory of Revered Wade Blank. Reverend Blank and 19 other members of a disability advocacy group blocked a RTD East Colfax Local bus on July 5 and 6, 1978. The RTD Board of Directors subsequently voted to begin purchasing wheelchair-accessible buses, and by 1985 Denver became the first major metropolitan area in the United States to provide wheelchair-accessible service on all Local buses. The site was re-dedicated in 2005 to commemorate the 15th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act.]

Americans with Disabilities Act (1990)

Disability historian, Lennard Davis, argued in his book Enabling Acts that if the courts had upheld the spirit of section 504, then the United States never would have seen the Americans with Disabilities Act. Yet, through the 1970s and 1980s, the courts increasingly sided with businesses and institutions who claimed accommodations to be too burdensome to enact. It became clear that more comprehensive, specific, and enforceable legislation was needed.

Disability historian, Lennard Davis, argued in his book Enabling Acts that if the courts had upheld the spirit of section 504, then the United States never would have seen the Americans with Disabilities Act. Yet, through the 1970s and 1980s, the courts increasingly sided with businesses and institutions who claimed accommodations to be too burdensome to enact. It became clear that more comprehensive, specific, and enforceable legislation was needed.

The passing of the ADA required collaboration and herculean efforts of a wide array of groups working on the inside and outside of Washington D.C.. Many people worked hard to write and garner support for the ADA.

We'll talk more about the ADA and what all it entails later in this training!

[Image shows President George Bush in a suit sitting at a desk and signing into law the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 on the South Lawn of the White House. Evan Kemp of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and Justin Dart of President's Committee on Employment of People with Disabilities, both white men, are sitting on either side of Bush. Dart wears a cowboy hat. Reverend Harold Wilke, a white male in a cassock, and Swift Parrino of the National Council on Disability, a white woman with short blond hair, stand behind Bush.]

Sources:

Davis, L. (2016). Enabling acts. Boston: Beacon Press.

Mccormick-Cavanagh, C. (2018, July 4). Remembering Gang of 19 forty years after Denver protests changed accessibility. Westword. Retrieved from https://www.westword.com/news/disability-protesters-gang-of-19-remembered-in-denver-10496346#:~:text=Led%20by%20Wade%20Blank%2C%20a,19%20started%20shocking%20the%20world.

Lesson 1 Part B: Activity

Your Turn! Discussion Participation

What moments or people in disability history stand out to you? When you come to our next Zoom meeting, be prepared to talk about a person or event in disability history of your choosing.

What moments or people in disability history stand out to you? When you come to our next Zoom meeting, be prepared to talk about a person or event in disability history of your choosing.

If you need some guidance, consider looking up one the following events and/or people: Deaf President Now (I. King Jordan and Gallaudet University), Capitol Crawl (Tom Olin, Anita Cameron, Jennifer Keelan), Disability Pride Parade (Karen Thompson) or dig a little deeper into the events discussed above such as 504-Sit In (Judy Heumann, Kitty Cone, Brad Lomax); Americans with Disabilities Act (Justin Dart, Evan Kemp, Lex Frieden). If you want to spend more time learning about the disability rights movement, check out documentaries like Crip Camp (on Netflix), Colorado Experience; The Gang of 19 on PBS (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=papy-GT_Ejo) or When Billy Broke His Head (Regis Library--DML Media Rm).

Arguably, the independent living movement propelled the contemporary disability rights movement forward and started a chain of events that eventually led to the passing of the ADA. The independent living movement can be seen as an anti-institutionalization movement. The movement is a rebuke of a dark U.S. history of removing people with disabilities from mainstream society and placing them in nursing homes, specialized schools, mental institutions, and prisons. The independent living movement aims to give people with disabilities options for living in a home and in a community with self-control and self-determination as well as medical care and other resources.

Arguably, the independent living movement propelled the contemporary disability rights movement forward and started a chain of events that eventually led to the passing of the ADA. The independent living movement can be seen as an anti-institutionalization movement. The movement is a rebuke of a dark U.S. history of removing people with disabilities from mainstream society and placing them in nursing homes, specialized schools, mental institutions, and prisons. The independent living movement aims to give people with disabilities options for living in a home and in a community with self-control and self-determination as well as medical care and other resources.

The 504 sit-in spurred progress, but many institutions found ways to drag their heels. Transportation companies often cited the high costs of accommodating people with disabilities as a reason to delay substantial changes to their services. The expensive and inconvenient options for transportation left available to people with disabilities spurred members of the country's second Independent Living Center (in Denver, Colorado) to protest against inaccessible public transportation.

The 504 sit-in spurred progress, but many institutions found ways to drag their heels. Transportation companies often cited the high costs of accommodating people with disabilities as a reason to delay substantial changes to their services. The expensive and inconvenient options for transportation left available to people with disabilities spurred members of the country's second Independent Living Center (in Denver, Colorado) to protest against inaccessible public transportation. Disability historian, Lennard Davis, argued in his book Enabling Acts that if the courts had upheld the spirit of section 504, then the United States never would have seen the Americans with Disabilities Act. Yet, through the 1970s and 1980s, the courts increasingly sided with businesses and institutions who claimed accommodations to be too burdensome to enact. It became clear that more comprehensive, specific, and enforceable legislation was needed.

Disability historian, Lennard Davis, argued in his book Enabling Acts that if the courts had upheld the spirit of section 504, then the United States never would have seen the Americans with Disabilities Act. Yet, through the 1970s and 1980s, the courts increasingly sided with businesses and institutions who claimed accommodations to be too burdensome to enact. It became clear that more comprehensive, specific, and enforceable legislation was needed.